The Federal Indian Boarding School Truth Initiative – A Breakdown

One June 22, 2021, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, issued a memorandum creating the Federal Indian Boarding School Truth Initiative. This new initiative is the first formal federal investigation into the boarding school system in the U.S., and was prompted by the discovery of 215 unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada. (Since that initial discovery, two additional collections of unmarked graves have been found in Canada at the sites of the former Marieval Indian Reservation School in Saskatchewan and the St. Eugene’s Mission School in British Columbia.)

Cushman Indian School, Tacoma, WA, 1918. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

So, what exactly is the Federal Indian Boarding School Truth Initiative, and what does it seek to do?

Secretary Haaland’s memo announcing the initiative outlines the history of boarding schools in the United States, underscores their assimilationist objectives, cites the abuse of students at many of these schools, and acknowledges the trauma experienced by generations of boarding school survivors and their families. The memo points out the need for closure for families whose loved ones died at boarding schools, and describes the challenges of collecting boarding school records, which are spread out across the country or, in some cases, completely missing. (For more on conducting research with these records, click here)

To address these issues, the Interior Department will specifically investigate the “loss of human life and the lasting consequences of residential Indian boarding schools.” This will include the documentation of boarding school facilities and burial sites associated with them, and the identification of the children buried at these locations

This investigation will have three phases. The first will focus on the collection of historical records from the National Archives and Records Administration, the American Indian Records Repository, and those maintained by non-government organizations, including churches or missionary groups. In the second phase, the Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs will meet with representatives from Tribal Nations, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians to discuss the future protection of cemeteries and burial sites in which boarding school students were interred. In the final phase, a report detailing these findings and future necessary steps will be submitted to Secretary Haaland. The report is expected by April 1, 2022.

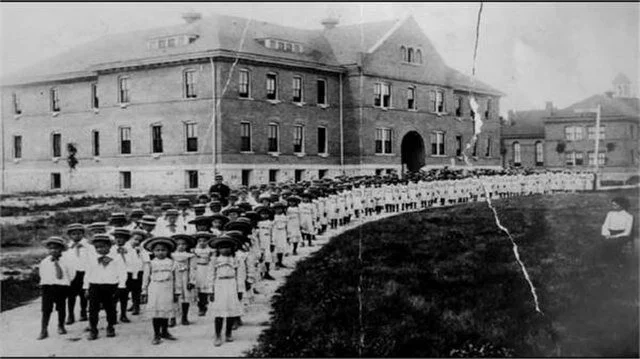

Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial School, Mount Pleasant, MI, circa 1910. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

This is an incredible step toward uncovering the history of the boarding school system in the U.S., and in acknowledging the generational trauma still experienced by Indigenous families across the country. That said, I do have some questions about the process and outcomes of this initiative.

· I am curious whether there will there be any enforcement mechanisms to require non-governmental organizations to comply with the records requests submitted by the Boarding School Truth Initiative. What happens if specific religious orders say no? Or if federal archival repositories do not provide the records the Interior Department is looking for?

· Conversely, will materials I have been looking for unsuccessfully for years suddenly turn up once more resources are dedicated toward their discovery? (Or once another federal agency is actively looking for them?) In my experience, not all materials within collections are properly organized, and in some cases repositories are not completely certain which records they have on hand. Maybe this investigation will help this situation or at least highlight the need for more funding and better archival oversight.

· Will the American Indian Records Repository (AIRR) become more transparent as a result of this effort, and potentially more accessible to tribal members and the public? As I have written about before, this organization has a lot of materials on the Stewart Indian School, but is basically closed to public inquiries about its collections.

· Once the investigation concludes, what happens next? Will there be a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, like in Canada, or a different mechanism to acknowledge how much the boarding school system continues to impact Indigenous nations?

· And finally, will this effort be decried as another effort to besmirch U.S. history, as happened with the New York Times 1619 Project? Will it become a punching bag for politicians and media figures who consider any digging into the unpleasant parts of U.S. history to be un-American or unpatriotic? (For the record, uncovering previously marginalized histories is neither of these things.)

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for more updates.

Samantha