Investigating Boarding School Crimes: Fort Lewis, Colorado

In May 2018, I was in Washington, D.C. at the National Archives doing research in conjunction with the Stewart Indian School Cultural Center & Museum, and reviewing material in Bureau of Indian Affairs education files. One set of items on my list was particularly intriguing: “Briefs of Investigations, 1898-1911,” which consisted of 2 bound volumes.

These books described investigations that occurred at 19 different on- and off- reservation boarding schools between 1898 and 1906. They are unique because official accounts of inappropriate or illegal incidents that occurred at boarding schools are rare, and those that do exist are generally spread out among regional archival collections.

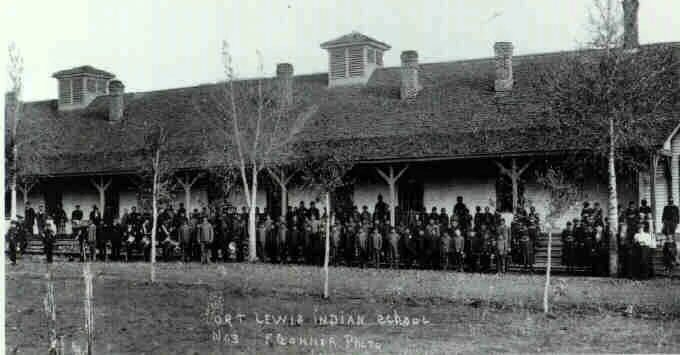

Fort Lewis Indian School, 1895. Image Credit: Fort Lewis College.

Fort Lewis Indian School: Background and Context

Among the varied types of incidents investigated by the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) during this period were a series of events that occurred in 1903 at the Fort Lewis Indian School in Colorado. This case illustrates how investigations were organized at the turn of the 20th century, how feedback from Indigenous and other external sources factored in, and how the OIA responded to accusations against boarding school personnel. It also demonstrates that the Office of Indian Affairs knew about abuses occurring at boarding schools across the country during this time period. It shows how federal officials responded to the claims of boarding school employees and students, and examines the extent to which they covered up or ignored alleged violence against Native children. At the same time, it also highlights the willingness of Indigenous students to speak out against their abusers, even as they were discredited or their allegations ignored.

The Fort Lewis Indian School was an off-reservation boarding school that opened in 1892 in Colorado. Thomas Breen, the school superintendent at the time of the investigation, had served in his position since 1894. The school enrolled students primarily from the Southern Ute, Navajo, Apache, and Pueblo nations. It followed the strict assimilationist programs mandated by the federal government in the late nineteen and early 20th centuries, which included basic courses in English and math, along with hours spent on gendered vocational training. By 1903, approximately 300 children were enrolled at the school, and Superintendent Breen had plans to expand the school grounds and enroll up to 1000 students. This never happened, and by the time the school closed in 1910 it had had an average daily attendance of just 35 students.

In 1903, a school employee named John R. Hughes, who worked as a blacksmith, was fired for “drunkenness and inefficiency” by Superintendent Breen. After his dismissal, Hughes made a series of accusations against Breen to the Denver Post, which printed multiple articles about the school beginning on April 22, 1903. These articles contained specific and disturbing accusations and became national news.

Dr. Thomas Breen, Superintendent of the Fort Lewis Indian School, pictured circa 1903. Image Credit: Fort Lewis College

The Accusations at Fort Lewis

In April 1903, the Office of Indian Affairs dispatched an investigator to the Fort Lewis boarding school to explore the allegations printed in the Denver Post. The OIA based its investigation on the Denver Post articles, reporters’ research notes, which it requested and received from the newspaper, and an on-site probe by Special Indian Agent Charles S. McNichols.

McNichols was dispatched to Fort Lewis on May 5th, and directed to investigate the following accusations:

1. That Superintendent Thomas Breen ran the school in an inefficient manner due to chronic drunkenness.

2. That the drunkenness of school employees was permitted. Specifically, Breen and unnamed Fort Lewis employees were accused of procuring liquor from the nearby town of Hesperus every Saturday and engaging in a “drunken orgie” (sic).

3. That Breen engaged in “immoral conduct” with female students, including unspecific sexual contact, taking nude photographs of female students, and hitting students with a cane or a stick.

4. That Breen engaged in “immoral conduct” with Fort Lewis employees.

5. That Breen had “debauched” multiple female students and sent some home pregnant.

Image credit, left: Fort Lewis College, mid-1890s. Image Credit, right: Fort Lewis College, 1896.

Investigation Findings

McNichols interviewed 14 witnesses to these crimes, and concluded his investigation in July 1903, with the following findings.

The charge of drunkenness against Breen was described as “proven,” based on the testimony of seven school employees and an account of a road accident during which Breen was unable to manage a team of horses and was thrown from his carriage. Further, McNichols reported that the majority of current and former employees reported having seen Breen intoxicated on a regular basis. However, McNichols found no proof of weekly drunken orgies.

Breen was found guilty of “very outrageous conduct” related to an incident referred to as the “Montoya/Creager Affair.” According to the testimony of three laundresses at the school, Katie Creager, Beneranda Montoya, and Minnie Kennedy, on the night of March 2, 1902 Breen went to the room shared by Montoya and Creager and spoke to them in an “improper manner.” In the aftermath of this incident, Breen fired both women and, in conjunction with two other school employees whose testimony was deemed unreliable, started a rumor that he had entered the women’s room because he thought they were “entertaining boys.” Multiple witnesses discounted this story and supported that of the laundresses.

Based on the testimony of Indian Service employees, McNichols thus judged the accusations of drunkenness and immoral conduct against school employees as true. When it came to the allegations of impropriety against Fort Lewis students, however, McNichols was less convinced of their veracity. Notably, these accusations relied solely on the testimony of female Indigenous students.

In his report, McNichols asserted that “the charges of general immoral conduct and debauching the school girls” against Superintendent Breen were “not sustained.” McNichols met with multiple female students who had alleged misconduct, and informed OIA officials that all but two of them had recanted their statements. One of these women was described as “so vacillating, first making her accusation then denying the same and again admitting the same, that no reliability is to be placed upon her word.”

The second woman maintained that her accusations were true and, according to McNichols, repeated them multiple times, verbatim, while under oath. However, the fact that this woman remained in her position as a domestic employee with Breen’s family meant, according to McNichols, that she must not be telling the truth. Because these women did not behave in a manner McNichols deemed credible, they were classified as liars.

McNichols also seems to have taken a different approach in his questioning of these students. He noted that each was questioned multiple times about the details of their accusations, though this does not seem to have been the case with the employees at Fort Lewis whom he also questioned. This tactic of forcing a victim to repeat their story repeatedly may have intimidated these students or otherwise led them to recant or waver on the details of their experiences.

It is also unclear who was present during these witnesses’ testimony: McNichols was certainly there, as he did the questioning, but could other Fort Lewis employees, maybe even Breen himself, been there as well? Even if it was only McNichols questioning these students, the power imbalance between a student and an OIA official could have impacted students’ testimony. Given these circumstances, it’s impressive that one of the female students remained steadfast in her account. However, McNichols simply found another way to discredit her testimony by questioning her behavior in the months following the incident.

Similarly, the charge that multiple female students left the Fort Lewis school pregnant, possibly by Breen, was “not substantiated,” according to McNichols’ report. He noted that two women did leave the school pregnant, but that they had named other men as the fathers of their babies. McNichols also asserted that there was no evidence that Breen took nude photos of female students or that he hit them with a cane or stick. There is no additional information about how McNichols came to these conclusions.

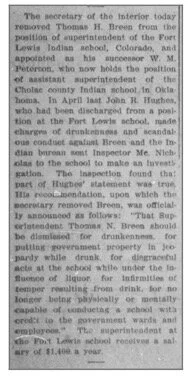

Article: San Juan County Index, NM, 8/7/1903; Image credit: Google images.

Outcomes

Ultimately, McNichols recommended that Superintendent Breen be removed from his position based on the charges of drunkenness and for “putting government property in jeopardy while drunk.” McNichols further stated that Breen had committed “disgraceful acts” while intoxicated, that he exhibited “infirmities of temper” while drunk, and that because of his behavior he was unfit to manage an OIA school.

At the same time, however, McNichols argued that because Breen was a victim of a “grossly sensational and exaggerated newspaper attack,” the OIA should issue a public statement explaining that he was removed from his position solely because of his drinking, and not because of his assault of female students or employees at Fort Lewis. Given McNichols’ conclusions on Breen’s behavior toward the laundresses, this assessment purposefully obfuscates the truth.

Ultimately, however, McNichols’ conclusions were accepted and announced. Newspapers in Colorado and throughout the country reported that Breen was, in fact, dismissed from his position, but only because of his drinking problem. Breen died in Colorado the following year, not having, as far as I can tell, issued a personal account of events at the school or his firing.

His reputation seems to have largely remained intact. One paper even printed an article announcing that it had been too harsh toward Breen, and issued an apology of sorts that lamented the impacts of alcoholism on Breen, who was described as an individual viewed with “high regard.” Breen’s behavior was not reported to the authorities and he was absolved from the majority of the accusations leveled against him. And just as a side note, to this day there is an unincorporated community in Colorado named after the former superintendent, who is described in the locale’s Wikipedia page as “a local educator.”

Gaps in the Investigation

This is where the official record of the 1903 investigation of the Fort Lewis Indian School ends. However, this brief glimpse into the manner in which this incident was handled raises many questions and highlights multiple gaps in the historical record. In terms of gaps, there are a number of sources that could shed light on this situation that are not included in the Briefs of Investigations report.

Foremost among these are Indigenous perspectives on this incident, including the statements of the female students who accused Breen of wrongdoing. According to the investigation report, these interviews were included in the final report, but were omitted from the Briefs of Investigations. Right now, I’m not sure whether they were destroyed, misplaced or otherwise lost.

Similarly, the six-page report on the Fort Lewis incidents references 42 separate “enclosures,” including affidavits and other witness testimonies connected with the investigation. McNichols notes these were included with the report he submitted, but none of them were included in the Briefs of Investigations book.

Archival gaps impact this story in other ways as well. I contacted the St. Louis branch of the National Archives, which stores federal military and personnel records, to get a copy of Thomas Breen’s personnel file. In my previous research, these personnel files have provided detailed information about investigations into employee behavior, and I hoped this would be the case again. However, I received a letter stating that Breen’s file was destroyed “per the records schedule.” This is confusing, since I have gotten records from other employees working for the Indian Service during this time, but regardless, it’s a dead end. I do plan to continue looking for the personnel records of others involved in the investigation.

Additionally, the charges mentioned in McNichols’ report (and in other reports in the book) are framed in euphemistic terms. We therefore have no idea what types of “immoral conduct” or “improper” incidents occurred at the school. Given the rampant physical, sexual, and emotional abuse that occurred at boarding schools, we can speculate, but remain unclear about what, specifically, happened at the Fort Lewis school.

From left to right: Salt Lake Herald, UT, 7/28/1903; Guthrie Daily Leader, OK, 7/30/1903; San Juan County Index, New Mexico, 7/31/1903. Articles collected via Newspapers.com.

Unanswered Questions

There are also a number of unanswered questions that remain regarding the investigation of such incidents at boarding schools during this time:

1. Was there a general set of procedures followed by Indian Service investigators in these situations?

2. Was this investigation handled differently because of the media attention the accusations garnered? Was it more thorough than others might have been because of this?

3. What should we make about the short period of time – 1898 to 1906 – represented in the Briefs of Investigations books? Abuses against students occurred throughout the periods various boarding schools were open, but it appears that efforts to document them collectively may have ceased early on. Researchers looking to uncover this painful aspect of boarding school history will have to piece these events together school by school, by speaking with survivors and their families, and mining the archives of specific schools to find them.

4. In a related inquiry, it is worth asking whether there was a conscious decision by the Indian Service to stop keeping records of these types of investigations. Were abuse cases documented and destroyed, due to their potentially inflammatory nature? And what happened to the testimonies and affidavits mentioned in the Fort Lewis case and others? Were these filed elsewhere, lost in a labyrinthine bureaucracy, or purposefully destroyed?

5. And finally, were any Indian school employees ever officially charged with the crimes they committed? In my work on the Stewart Indian School I have documented that school officials and local police worked together to advance the assimilationist objectives at these schools. Is it possible these relationships extend into covering up or ignoring school employee crimes, as well?

Going forward, I hope to answer at least some of these questions and to try and fill in some of these gaps. The testimonies of boarding school survivors and their families will be critical in these efforts, along with additional archival research. Telling the truth about this painful history, as well as highlighting Indigenous resilience and bravery in the face of almost unimaginable forms of abuse, is critically important, as is the need to hold the U.S. government accountable for the traumas it has engendered among generations of Native families.