Student Writings at the Stewart Indian School - Part 2

My previous post focused on the writings of Stewart Indian School students between the early 1900s and the 1940s. This post examines student writings between the 1950s and the closure of the school in May, 1980. These writings share important insights into student life at Stewart, and are, in some cases, the only opportunities for historians to hear directly from students about their experiences at the school. If you are interested, there is also a more extensive collection of student writings available for review at the Stewart Indian School Cultural Center and Museum in the Reflection Room. Check it out when you visit!

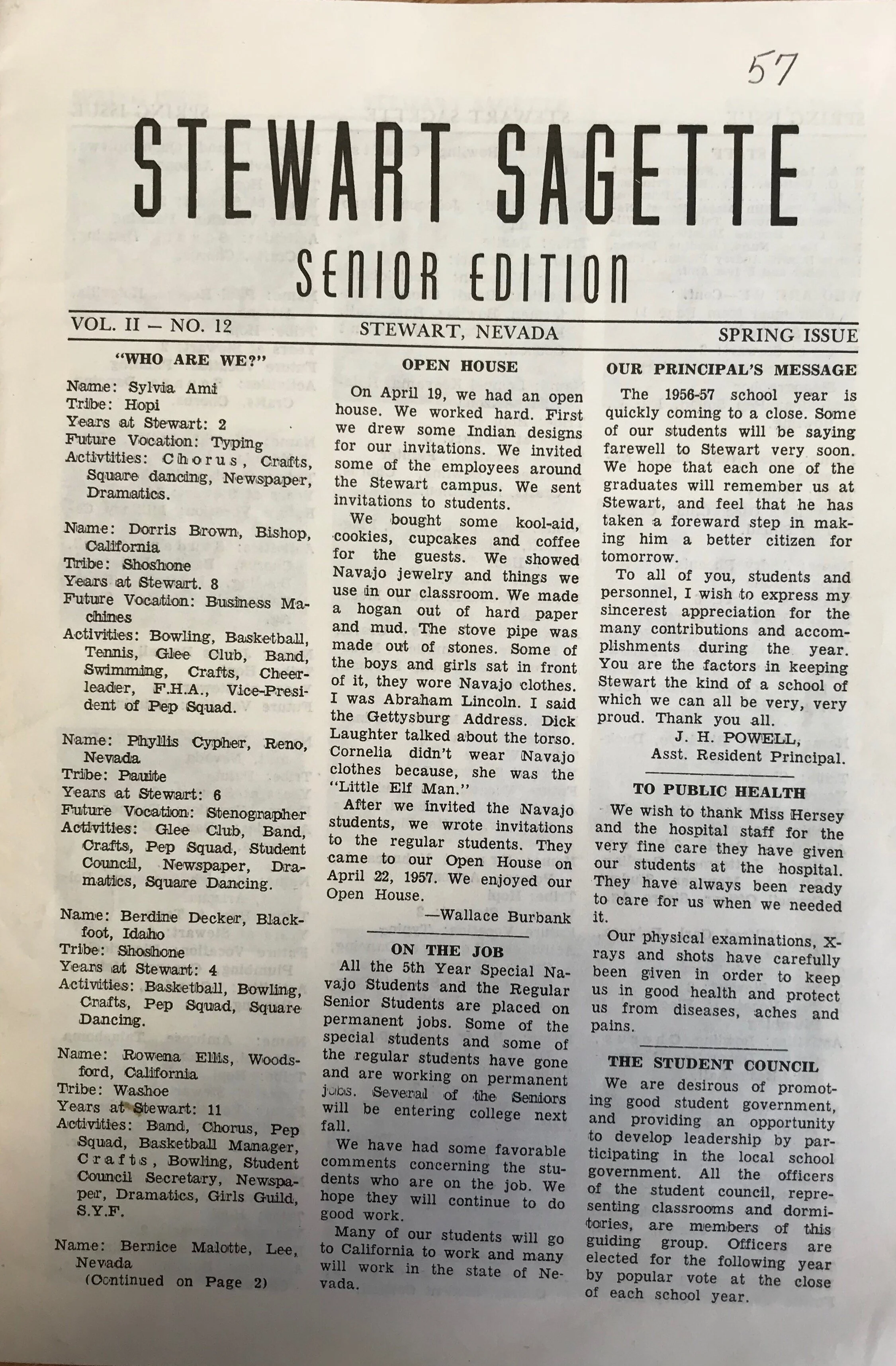

There were two student newspapers associated with the Stewart School in the 1950s. The first, The Stewart Sagette, focused primarily on the activities of students in the so-called “regular program” at the school, meaning students not associated with the Navajo Special Program (more on this below). The Sagette was written entirely by students and very little content about school employees was included in the paper. Instead, student reporters provided regular updates on academic and vocational programs and various events at the school. There was little editorializing in this newspaper, through students did find a way to share their future professional objectives, profess their tribal identities, and speak to one another using coded language.

To give an idea of what types of articles were in the paper, the November-December 1954 edition of The Sagette included an article about students’ pen pals in England and a description of a mock election at the school, in which students were registered for a political party and voted for the local and state representatives actually on the ballot in Nevada that year. In 1955, students wrote about performing tribal dances at basketball games and in the community, and the school’s Indian Club, which organized these activities.

Spring editions of The Sagette included lengthy sections devoted to graduating seniors, who shared their future aspirations in a “Senior Prophecy,” listed their tribal citizenship, their length of attendance at Stewart, and jokingly willed various items, personality traits, and campus locations to those remaining at the school. In May 1953, the Senior Prophecy column speculated that Stanley Alvarez would build the first spaceship that traveled to Mars, Helena Jones would be the future general manager of the Bell Telephone Company, and that Madeline Domingues would cure the common cold. These students were clearly determined to move beyond the narrow expectations school officials had for them.

The spring 1957 edition of The Sagette also included a gossipy section titled “Less We Forget,” which shared a lot similarities with the gossip column students published in the 1940s. Items in this section gently teased Stewart students, and included the following, sometimes cryptic, entries:

“Ernest Nahnacassia’s reputation for speed on the track field must have gone to his head – he keeps trying for speed during rhythm drills in typing”

“Teachers should be made to wear bells. I’m sure Sylvia and Vernon are in favor of it. How about it, kids?”

“Roland, what can be so special about that second tree stump by the ECA store?”

During the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s, Stewart hosted thousands of Navajo students enrolled the Navajo Special Five Year Program. Navajo students had their own school newspaper, The Sherman Bulletin, which was published by the Sherman Institute, a Native American boarding school in Riverside, California. This newspaper featured articles, letters, jokes, and stories written by students enrolled in each of the eleven off-reservation boarding schools that housed Navajo students. The articles written by Navajo students in The Sherman Bulletin show how students spent their days and describe the lessons teachers wanted Navajo students to learn. The Sherman Bulletin contained fewer opinion pieces and lacked the many assertions of racial equality found in other Stewart student papers.

However, a number of the articles underscored the frustration some Navajo students felt with the education they were offered at the Stewart School, which largely consisted of remedial coursework and vocational training. Student Peterson Herder emphatically articulated his desire for more education in a January 1956 article in The Sherman Bulletin in which he wrote, “I want to get more education. I try hard this year because I want more education. All of us should try hard in school. Try hard and we learn everything we can. I want more education.” Graduating student Frances Notah shared similar sentiments in an article published the following year: “Soon the Fifth Years will be leaving for our permanent jobs. Maybe some of us are very happy to go out on the job. Some of us are unhappy to leave our school. For me, I don’t really know what to say about it. But I do know that I need more education.”

At the same time, however, Navajo students also wrote about the extracurricular clubs they joined, their holiday parties, and field trips to Carson City for special events, like visits to the movie theater. Peter Castillo wrote about learning to cook in his home economics club, and discovering that he actually liked it, while Thomas Morris described having fun with the swimming club at Carson Hot Springs and learning different ways to float and how to tread water. Students played games at Valentine’s Day parties and celebrated the birthdays of teachers and fellow students. Navajo students also drew illustrations to accompany various articles (shown above), shared self-deprecating stories about their misadventures at school and with their families, and wrote jokes, all of which were published in The Sherman Bulletin. Among the jokes published was the following:

Kee: “Will you please get me a hot dog.”

Freddie: “With pleasure.”

Kee: “No Freddie, with mustard.”

The presence of assimilationist rhetoric was also widespread in some of the articles Navajo Special Program students wrote for The Sherman Bulletin. Student Jimmy Ayze, in a 1955 article, emphasized the importance of Navajo students speaking English as much as they could, even if they were only in their first year of school. He asserted, “Some of us are not using good English because we don’t try to use English,” an assertion he noted was also made by one of his teachers. After further encouraging his fellow students to use English more, he recommended that students “Just forget about the Navajo language and use English all the time.” When the Navajo program ceased at the end of the 1950s, The Sherman Bulletin ceased publication, too.

Unfortunately, I have not yet found any editions of student newspapers or other types of writings from the 1960s. However, the Stewart Indian School Cultural Center and Museum does have a collection of student newspapers from the early 1970s through 1980, the final year the school was open. This newspaper, The Warpath, chronicles student life at Stewart and appears to be written primarily by students. It features strongly worded student editorials and varied forms of expression, including poetry and tribal stories. Pupils also expressed disagreement with school and federal policies in the publication and advocated for reforms at the school.

In one such case, students Lois George and Valerie Jefferson wrote about several students recently in trouble for running away from the school and drinking alcohol. In the October 5, 1979 edition of The Warpath, the authors noted that, because a detox space at the school was recently closed, these students were sent first to the Carson City police station, where they were booked for their offenses, and then sent to Wittenberg Hall juvenile detention facility in Reno. George and Jefferson felt it unfair for students to have such offenses noted on their permanent records, and advocated that the detox area be reopened to deal with such incidents.

The Warpath was also a forum for critiques of colonization and appeals for tribal unity. An article published in October 1978 addressed the conclusion of Indian Claims Commission activities, and referred to its efforts as trying to resolve the “unconscionable dealings” between the U.S. and Native peoples. The article further expressed opposition to the transfer of remaining claims to the U.S. Court of Claims, which was described as a “hard bargainer” and unlikely to side with Native plaintiffs. Other critiques were inspired by a film on Spanish and French colonization in the Americas shown in an English class. In the December 12, 1978 edition of the Warpath, student Daniel Velasco wrote that, if not for colonization, “…we, the so-called “Indians” would still be living the same lives as we did back then,” and that any changes would have been “our concern.”

Another student, Arnold Rios, wrote an editorial in February 1980 in which he called for Red Power and Indian unity on campus. He praised the existence of tribal clubs at Stewart, but suggested that a more inclusive ‘Indian Club’ would allow students to “start standing up with each other” and “unite.” He added that, although Native people were a minority in the U.S., if united together they could be a “powerful minority and we could determine our future for ourselves.”

Students also articulated their opposition to the closure of the school in articles published in the Warpath, and expressed skepticism regarding the BIA’s proposed action. Just after the possible closure was announced, students speculated about the federal government’s ulterior motives regarding the closure. One wrote, “I think they want to close Stewart because the government is after the land…all they want is land.” Another editorial written in May 1980, in what turned out to be the final edition of the Warpath, opposed the closure of the school on the grounds that it would leave Stewart employees jobless and deny Native students their educations. Students were also cynical about the motivations behind the potential closure. Accordingly, the closure was explained by the following logic: “It’s a case where Indians have something good going for them, and the white people want it.”

Throughout its history, Stewart students found ways to express their creativity and personalities while participating in an educational system that sought to erase their Indigenous identities. Newspapers and other mediums offered many opportunities in this regard, and reading through student writings underscores the abilities, resilience, and adaptability of students throughout the nine decades the Stewart Indian School remained open.

Sources:

Stewart Indian School Cultural Center and Museum Collection.

National Archives – Pacific Region, San Bruno, California.