Student Writings at the Stewart Indian School - Part 1

While researching my dissertation on the history of the Stewart Indian School, I read several collections of student writings that helped me better understand how some students experienced their time at Stewart. Through these writings, I discovered some of the sophisticated ways students pushed back against school officials, and how they expressed themselves and their aspirations through articles in school newspapers, speeches, gossip columns, jokes, and art. These mediums gave students the space to address issues relevant to their experiences while also illustrating different aspects of their lives at Stewart.

It is almost impossible to determine the specific circumstances under which each article, speech, or other work was written, or how much Stewart faculty members might have edited, encouraged, or otherwise interfered with the aims of student authors. Also, it is important to acknowledge that newspapers and other forms of student writing were themselves used as part of the assimilation process: encouraging participation in writing newspaper articles or commencement speeches was a means of forcing students to use English versus their Indigenous languages. Despite these uncertainties, I believe student writings are an invaluable source of information about daily life at Stewart and an indication of how the school changed in some ways, but remained static in others, over many decades.

So what did Stewart students write about?

Perhaps surprisingly, during the early decades after the school opened, when Stewart students experienced intense periods of assimilation and white supremacist rhetoric, students used the school newspaper to express their equality, resolve, and share future plans that did not necessarily reflect the assimilationist ideals of school officials.

Emma McGeary, for example, who graduated from Stewart in 1904, wrote in the Class Prophesies section of the July 1904 edition of the Indian Advance school newspaper that she planned to enroll in college and become a teacher, and that she would “show her skill in teaching as well and as orderly as any white man or woman.”

That same year, Stewart graduate Jack Mahone shared a comprehensive account of his post-graduation plans. He wrote:

“After I leave school I am going to build me a little house at first and of course a little farm. After ten or twelve years of hard working the farm and the house will be a great deal larger...When time comes for cutting hay I’ll hire some man to help me get all my hay in and this will be the first crop, then when the second crop is ready I’ll hire some more men to help me get in the hay…”

In one sense, Mahone embraces the assimilationist vision of federal officials who ordered Native peoples to live on and farm individual land allotments. At the same time, he also rejects the white supremacy modeled in boarding schools by stating his intent to manage his farm as a business, independently, rather than going to work for someone else.

Female Stewart students also identified post-graduation plans that defied the expectations of school officials. 1904 graduate Lizzie Dutch planned to be a laundress and manage her own laundry business. Emma Bobshaw planned to be the head nurse at an Indian school, where she would demonstrate she was “equal to any white woman as far as nursing is concerned.”

Pansy Henry intended to become a seamstress and create her own unique dress patterns, and,

“After many years of successful work, she will think of her Washoe tribe. She will go out among them and tell the folks to send their children to school to learn what it means to have an education.”

And Emma McGeary, mentioned earlier, rejected notions of white supremacy and stated her plans to attend college, teach in a public school, and, later, to “be employed in an Indian school as [a] teacher where she will remain and help the Indians.”

During subsequent decades, students expressed their views and interests through other forms of writing as well. I was particularly by struck works from the mid-1930s written after the passage of the “Indian New Deal.” Many of these writings reflect school officials’ encouragement that students should embrace and explore their tribal histories and cultures.

One example from this period is a speech delivered by graduating student Ethel Steele. Rather than focus on the accomplishments of individual students, her defiant speech emphasizes the historical contributions of Indigenous peoples and demands their recognition. Steele wrote:

“Had it not been for the Indian trails and much used routes of travel, the occupation of the North American continent would have taken a much longer time. These trails along difficult places marked the routes of the westward moving pioneers, and the same is true of the portages connecting the natural waterways. The buffalo trails became Indian trails and they in turn became the trade trails…The trading posts reached by these trails were on the sites of former Indian villages and many of these have grown into some of our most modern cities…The Indians are as much a part of this great country as the rivers, the deserts, the mighty mountains. The Indian – if you seek his monument look about you.”

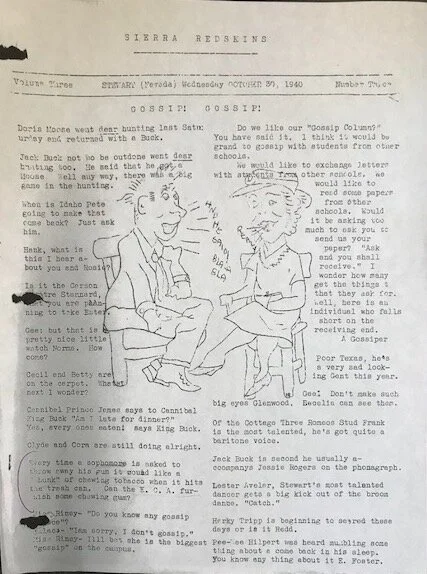

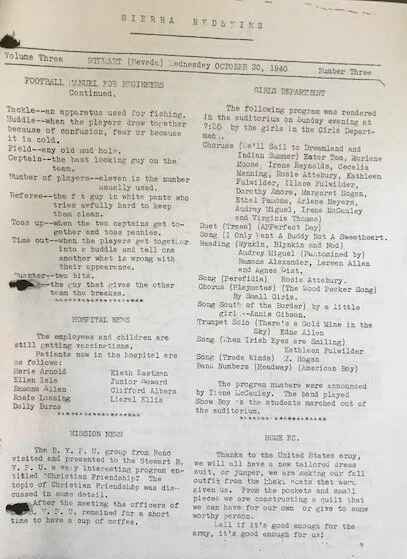

The Stewart Indian School newspaper during this period also reflected new forms of student expression, including cover art and cartoons drawn by students (which you can see below), a school gossip column, and an extensive section devoted to school sporting events. A new iteration of a newspaper was also created in the late 1930s or 1940s, which bore the unfortunate name, Sierra Redskins, and reflected more student interests than in previous decades. Though the paper included columns written by school officials, pronouncements on federal policies, and, during World War II, calls for students to aid the war effort, student personalities emerged in a manner that differed significantly from previous publications.

One of my favorite examples of this is the Gossip Column contained in the paper, in which writers told jokes, speculated about their fellow students’ love lives, and poked fun at teachers. And, as you can see here, they also included some tongue and cheek drawings of people in the act of gossiping. But going beyond these types of statements are critiques of the school – comparing, for example, the type of gum sold at the student store to chewing tobacco and suggesting that the meat cooked in the kitchen was cat – and a desire to connect with other boarding school students. In the October 1940 issue of the newspaper, the gossip page included the following comments:

“Do we like our “Gossip Column?” You have said it. I think it would be grand to gossip with students from other schools. We would like to exchange letters with students from other schools. We would like to read some papers from other schools. Would it be asking too much to send us your paper?”

Interestingly, in at least one case during this period, the newspaper published a critique written by a former student who suggested that Stewart students had forgotten their histories and were trying too hard to be something they were not. In the March 7, 1941 issue of the newspaper, Stewart alumna Nellie Shaw Harner described students as “ashamed” of a school chant in which students yelled the names of the Native Nevadan nations whose children originally comprised the student population at the school. Accordingly, Shaw wrote in the newspaper:

“This year I wondered why I hadn’t heard one of the finest school yells. At the tournament last week I asked that that yell be given because it is Indian and isn’t just a copy of the yells of high schools around here. To my surprise I was told the girls were ashamed of it. I felt like I was just stunned…ashamed, not of the yell, nor myself, but of Indian students who are ashamed of being Indians; Washoes, Paiutes, Shoshones…I fear the students want to be too much “white,” forgetting the finer qualities of the true Indian. I felt this more when a yell was attempted at the university gymnasium, and it was a failure.”

Though a current student did not levy this criticism, Harner’s observations indicate that at least one member of the broader Stewart community was uncomfortable with the level of assimilation still occurring at the school during this time. That the paper’s editors agreed to publish this letter suggests that Harner was, perhaps, not alone in harboring such sentiments.

Come back next week to read more about student writings from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s!

- Samantha

Sources:

Jacqueline Emery, Ed. Recovering Native American Writings in the Boarding School Press (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), 2017.

Stewart Indian School Cultural Center and Museum Collection.

University of Nevada, Reno, Special Collections.